Australia continues to rely on billboard-style and cinematic advertising to promote itself as a destination. This approach, used for decades, presents a national image built around iconic sites and curated visuals.

While this style may appeal to tourism bodies because of the celebrity-fronted content and central control, it is increasingly out of step with how modern travellers plan their journeys.

In 2025, travellers are scrolling TikTok, watching Instagram reels, and browsing peer reviews. Tourism campaigns should meet people where they are.

Authenticity beats curated content

Social media is a central source of travel inspiration, particularly for Gen Z and millennials, according to a global survey of 20,000 respondents across all age groups.

Almost 90% of young travellers discover new destinations through TikTok, and 40% say they have booked a trip directly because of something they saw on the platform.

What matters most is not just reach, but trust.

Influencers shape behaviour from desire to booking and post-trip sharing. Their impact rests on perceived authenticity. Real people telling stories resonate more than stylised ads.

Storytelling sits at the heart of this shift, and tourism providers can engage in this form of storytelling, too. Airbnb’s Host Stories campaign invites hosts to share personal narratives through short videos and blog posts.

By highlighting real hosts and their daily lives, marketing moves beyond selling places and instead emphasises authentic, locally rooted connections that resonate with travellers.

It introduces travellers to places through personal experience, grounded in local knowledge and genuine connection.

User-generated content builds trust

A 2025 study found user-generated content enhances emotional connection and perceived authenticity with potential tourists.

Stumbling on a friend’s holiday photo or a short travel video in their feed can increase the appeal of a destination. Unlike traditional advertising, which requires deliberate placement, peer content can influence simply by appearing in everyday browsing.

Australia has used participatory storytelling before. One powerful example is Tourism Queensland’s 2009 Best Job in the World campaign, which invited applicants from around the world to compete for a six-month caretaker role on Hamilton Island in the Great Barrier Reef. All they had to do was submit a short video explaining why they were the right candidate.

The campaign went viral, attracting over 34,000 applicants from 200+ countries, millions of website hits and global media overage.

Its success was driven less by who eventually got the job and more by the anticipation and unusual premise. It stood out because of simplicity and inclusivity, inviting real people to be part of the narrative.

Yet, 16 years on, Australia’s national tourism campaigns still rely on cinema ads, billboards and polished TV commercials built around icons such as Uluru and the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

From storytelling to story-sharing

The long-running Inspired by Iceland campaign consistently encourages locals to share authentic travel memories, cultural insights and personal stories.

Iceland Hour, launched in June 2010, saw schools, parliament and businesses pause for a coordinated social media push. Citizens and international supporters posted more than 1.5 million positive, personal messages across social media in a single week.

The campaign helped rebuild confidence after the Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption, and contributed to a 20% year-on-year rise in tourist arrivals.

Finland’s Rent a Finn campaign, launched in 2019, embraced a similarly human-centred approach. Showcasing ordinary people rather than cinematic landscapes, the campaign reached 149 countries, contributed €220 million in additional tourism revenue and reinforced Finland’s reputation as the “world’s happiest country”.

The United Kingdom’s Great Chinese Names for Great Britain campaign in late 2014 invited Chinese audiences to propose Mandarin nicknames for 101 British landmarks.

Suggested names, such as “Strong Man Skirt Party” for a kilted parade or “Stone Guardians” for Hadrian’s Wall, were featured on Google Maps and Wikipedia.

The campaign attracted more than 13,000 submissions, sparked widespread engagement on Chinese social media and was followed by a 27% increase in visits from China. It was worth an estimated £22 million boost to the UK economy.

Storytelling as a sustainability strategy

Participatory storytelling is not only more engaging, it can also be more sustainable.

Japan’s Hidden Gems campaign redirects tourist traffic away from overcrowded areas like Kyoto and Tokyo by spotlighting lesser-known destinations through locally led narratives. These stories promote slower travel, distribute benefits more evenly and reduce pressure on fragile ecosystems.

Australia faces a similar challenge. Our global image is still anchored to a handful of spectacular but vulnerable icons.

Yet tourism is about more than selfies in front of sandstone or coral. By inviting regional communities and visitors to tell their stories, we could shift attention beyond brochure highlights and encourage deeper, more diverse engagement.

There is also a strong economic case for prioritising emotional connection. Research shows when travellers form personal bonds with a place – through memorable, localised experiences – they are more likely to return, recommend it to others and stay longer.

Tourism is a relationship, not a product

Visitors are not passive consumers of postcard moments but active contributors to a shared story.

Australia’s tourism strategy should reflect this. This could mean amplifying visitor photos and videos on official platforms, inviting local communities to co-design campaigns, and drawing on authentic user-generated content rather than polished advertising and cinematic masterpieces.

That means letting go of perfection, embracing authenticity and trusting that the people who come here, as well as the people who live here, have stories worth sharing.![]()

Katharina Wolf, Associate Professor in Strategic Communication, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

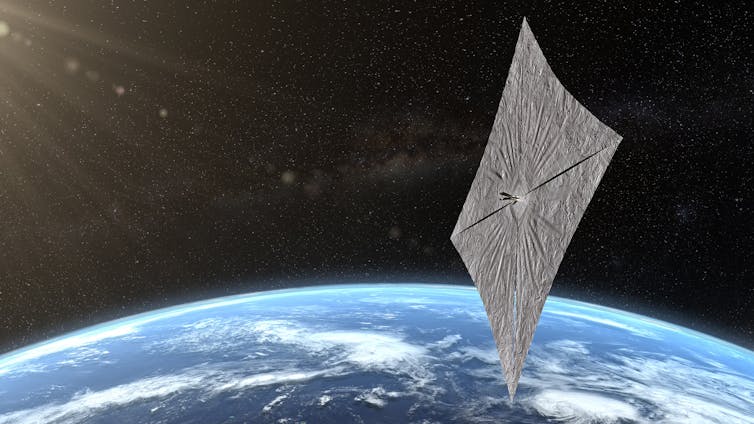

Can a new satellite constellation create sunlight on demand?

Can a new satellite constellation create sunlight on demand?

The Conversation,

The Conversation,