Nissan to invest $17.6 bn in EV development over next 5 years

World Athletics C'ships: United States wins three of four relay titles on final day in Tokyo

World Athletics Championships: Neeraj Chopra eyes repeat of history in Tokyo

Oshikatsu, the fandom phenomenon Japan hopes can boost its flagging economy

Posters in Tokyo’s enormous Shinjuku railway station are normally used for advertising commodities like cosmetics and food, as well as new films. But occasionally you may happen across a poster with a birthday message and a picture of a young man, often from a boy band and typically with impeccable looks.

These posters are created by specialised advertising companies and are paid for by adoring fans. They are part of a phenomenon called oshikatsu, a term coined in recent years that is made from the Japanese words for “push” and “activity”.

Oshikatsu refers to the efforts fans engage in to support their favourite oshi, which can mean an entertainer, an anime or manga character, or a group they admire and want to “push”.

A considerable part of this support is economic in nature. Fans attend events and concerts, or buy merchandise such as CDs, posters and other collectables. Other forms of oshikatsu are meant to spread the fame of their idol by sharing content about their oshi, engaging in social media campaigns, and writing fan fiction or drawing fan art.

Oshikatsu developed out of the desire of fans to have a closer link to their idols. The combination of oshi and katsu first appeared on social media networks in 2016 and became widespread as a hashtag on Twitter in 2018. In 2021, oshikatsu was nominated as a candidate for Japan’s word of the year, a sign that its use had become mainstream.

Now, it has appeared on the radar of corporate Japan. The reason for this is a burst of inflation in recent years, caused by pandemic supply chain disruption and geopolitical shocks, that has caused Japanese consumers to reduce their spending.

However, with wages set to rise again for the third time in three years, the government is cautiously optimistic that economic growth can be rekindled through consumer-driven spending. Entertainment and media companies are looking to oshikatsu as a potential driver of this, although it is unclear whether the upcoming pay hikes will be sufficient.

A widespread phenomenon

Contrary to popular perception, oshikatsu is no longer the purview solely of subcultures or young people. It has made inroads with older age groups in Japan as well.

According to a 2024 survey by Japanese marketing research company Harumeku, 46% of women aged in their 50s have an oshi that they support financially. Older generations tend to have more money to spend, especially after their own children have finished education.

Oshikatsu also signifies an interesting reversal in terms of gender. While husbands in the traditional Japanese household are still expected to be breadwinners, in oshikatsu it is more often women who financially support young men.

How much fans spend on their oshi depends. According to a recent survey by Japanese marketing company CDG and Oshicoco, an advertising agency specialising in oshikatsu, the average amount fans spend on activities related to their oshis is 250,000 yen (about £1,300) annually.

This contributes an estimated 3.5 trillion yen (£18.8 billion) to the Japanese economy each year, and accounts for 2.1% of Japan’s total annual retail sales.

Oshikatsu will drive up consumer spending. But I doubt it will have the impact on the Japanese economy that the authorities are hoping for. For the younger fans, the danger is that government approval will kill any kind of cool clout, making oshikatsu less appealing to these people in the long run.

And if you support an oshi who has not yet made it, you may have a stronger sense that your support matters. Hence some of the spending will go directly to individuals, rather than to established corporate superstars. But it’s also possible that struggling young oshis may spend more of this money than established celebrities.

The international press is focusing either on the economic side of oshikatsu, or on the quirkiness of “obsessive” fans who get second jobs to support their oshi and mothers spending large sums on a man half their age. But what such coverage misses is the slow yet profound societal transformation that oshikatsu is a sign of.

Research from 2022 on people engaging in oshikatsu makes clear that “fan activities” address a deep wish for connection, validation and belonging. While this could be satisfied by friendship or an intimate partnership, an increasing number of Japanese young adults feel that such relationships are “bothersome”.

Young men are leading in this category, especially those who do not work as white-collar corporate workers with relatively stable jobs, the so-called salarymen. Many who work part time or in blue-collar jobs are finding it difficult to imagine a future in which they have families.

The tertiary sector is thus changing to accommodate an increasing number of services that turn intangible things such as friendship, companionship and escapist romance fantasies into paid-for services.

From non-sexual cuddling to renting a friend for the day or going on a date with a cross-dressing escort, temporary respite from loneliness can be sought on a per-hour basis. As a result, human connection itself is becoming something that can be consumed for a fee.

On the other hand, sharing oshikatsu activities can create new friendships. Fans coming together to worship their idols collectively is a powerful way of creating new communities. It remains to be seen how these shifts in the way people relate to each other will shape the future of Japan’s economy and society.![]()

Fabio Gygi, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

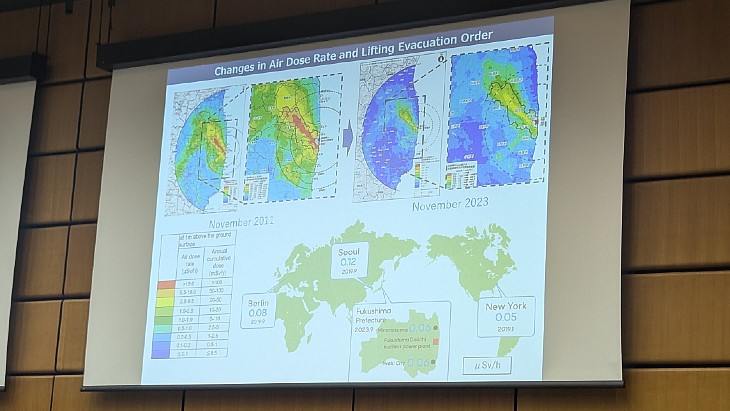

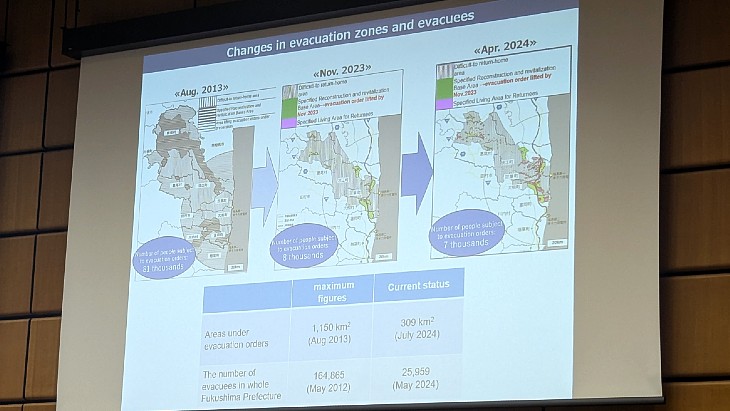

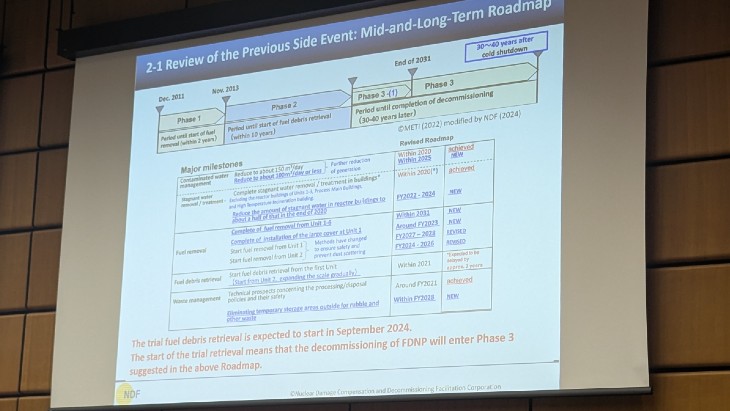

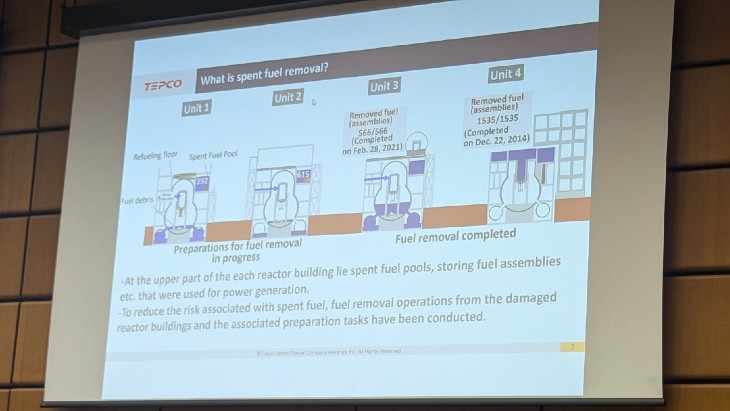

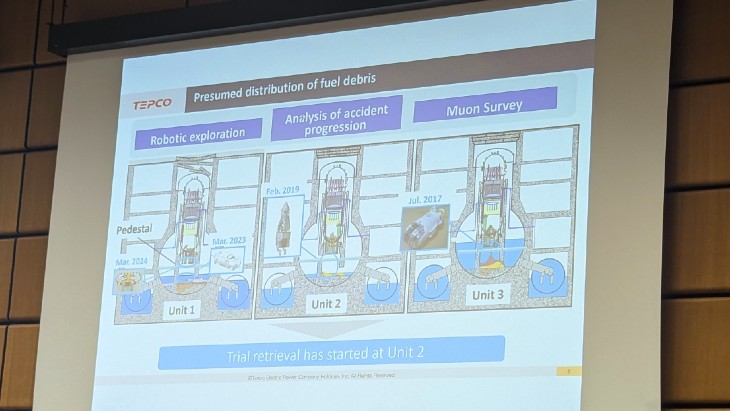

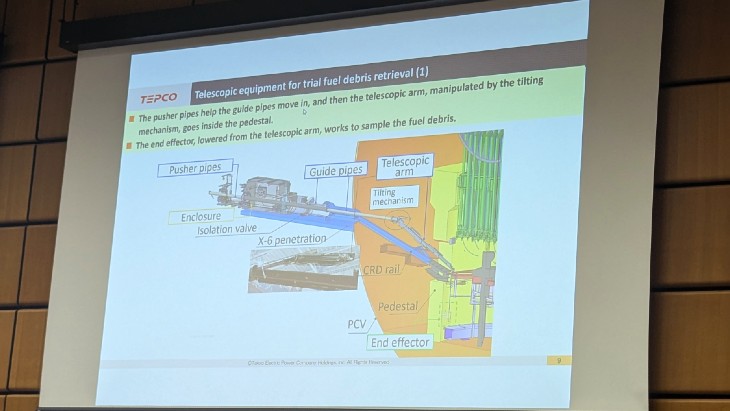

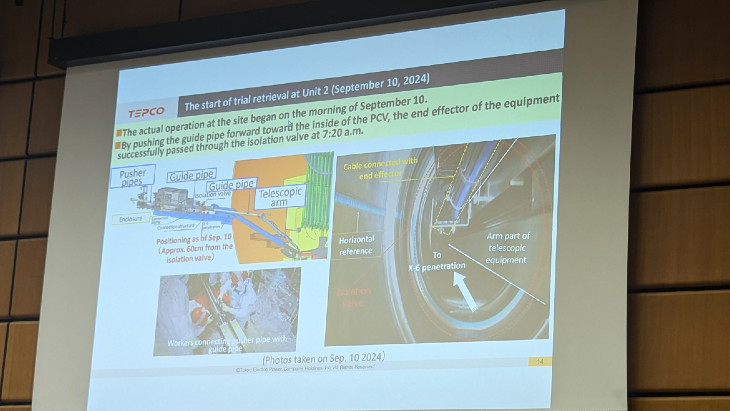

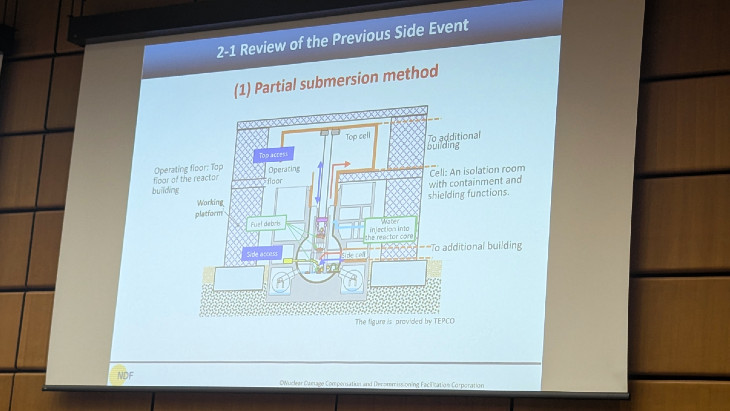

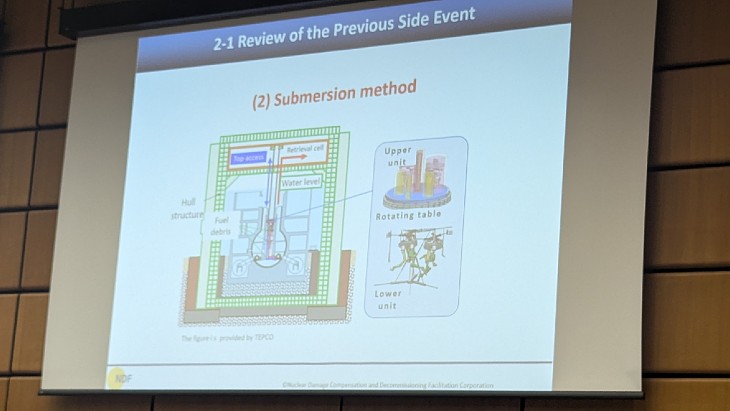

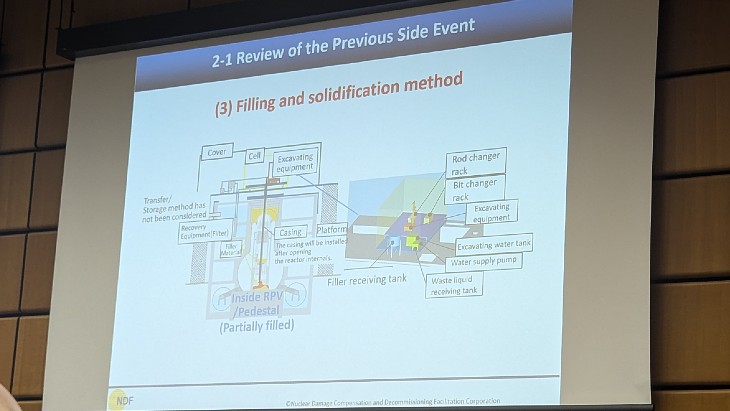

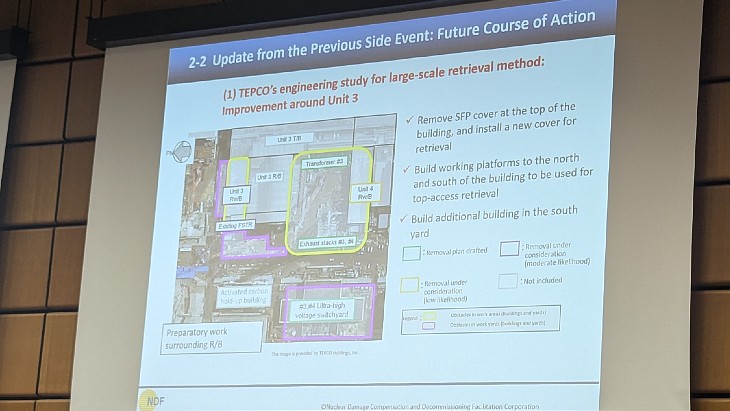

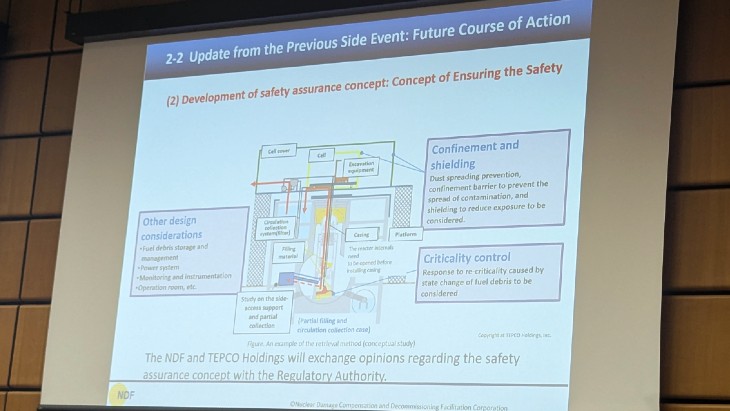

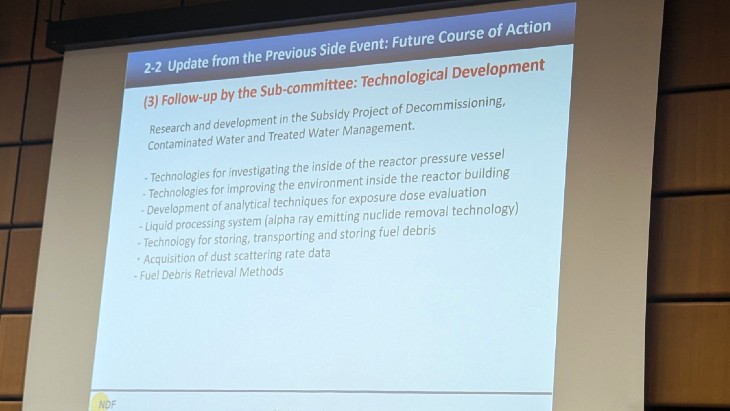

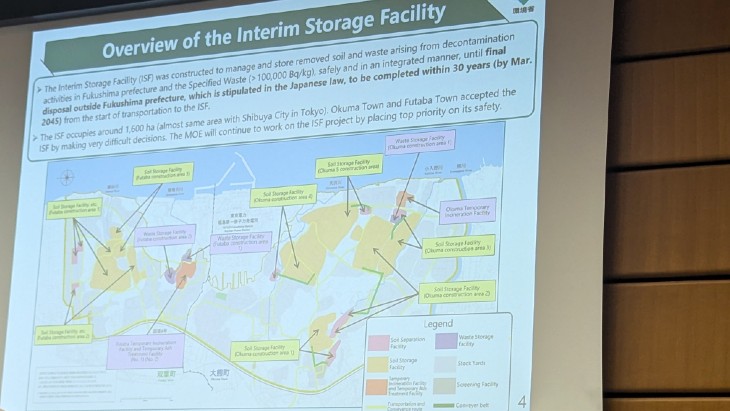

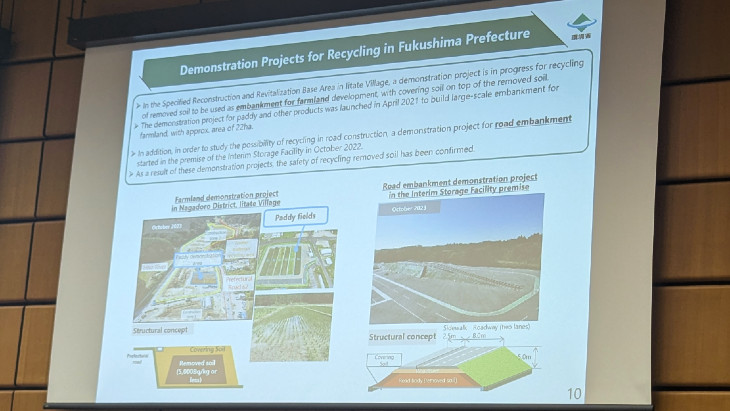

Fukushima Daiichi: How is the decommissioning process going to work?

(Image: Tepco)

(Image: Tepco)

Japan aims for increased use of nuclear in latest energy plan

Japan wants to host 2031 World Cup to fire up women's football

Japan issues emergency warnings issued for Kagoshima as typhoon nears

Why did Japan’s prime minister decide to step down? And who might replace him?

In a surprise announcement, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said today he would step down as leader of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) next month, bringing his premiership to an early end.

Since coming to office in October 2021, Kishida has struggled to overcome dire approval ratings.

The party has been dogged by revelations of ties to the Korean-based Unification Church in the wake of the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in July 2022, as well as a political fundraising scandal uncovered last November.

Kishida dissolved his own powerful faction in the party and pressured the largest conservative faction, formerly headed by Abe, to dissolve itself in the wake of the scandal. Up to 80 LDP members of the Diet (Japan’s parliament) were implicated, and four cabinet ministers resigned.

Public prosecutors investigating the scandal decided not to proceed with indictments against Kishida and seven other senior LDP figures, due to lack of evidence.

Just three months ago, Kishida vowed he would not step aside, instead pledging to push anti-corruption measures and other political reforms.

To try to stem the damage, the LDP passed a bill in the Diet in June to reform the political funds control law, but the opposition called it inadequate.

The chief of the Maritime Self-Defence Force also resigned last month over allegations he mishandled national security information, making things even tougher for the Kishida government.

In a poll in late July, 74% of respondents said they did not want Kishida to stay on as party leader after the LDP leadership election in September. With his public unpopularity remaining entrenched, he was unlikely to receive the backing of a majority of LDP Diet members in next month’s vote.

Widely considered a consistent foreign policy performer, Kishida had a series of strong diplomatic appearances in recent months. He attended NATO’s 75th anniversary summit in Washington, followed by an official visit to Germany. He then returned to Tokyo to host the Pacific Island Leaders meeting last month.

He had been due to embark on a tour of Central Asia last week, but cancelled the trip after a magnitude 7.1 earthquake struck Japan.

Rivals are already emerging

Kishida’s rivals have already started to position themselves for next month’s leadership election – and to become Japan’s new prime minister.

Shigeru Ishiba, a former defence minister and LDP secretary-general, regularly polls as the public’s preferred candidate. He has already announced he will run, with the backing of Kishida’s predecessor, Yoshihide Suga.

LDP Secretary-General Toshimitsu Motegi, who refused to dismantle his faction in the wake of the fundraising scandal, is also considered a potential contender. Digital Minister Taro Kono, one of Kishida’s opponents in the 2021 leadership race, is another.

Economic Security Minister Sanae Takaichi and Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa could also enter the contest. If either of them won, Japan would have its first female prime minister.

Challenges remain

Whoever replaces Kishida in September will then have to restore the LDP’s electoral fortunes before the next national election, due by October 2025.

Key to this will be reinvigorating Japan’s sluggish growth, which has shown the relative failure of Kishida’s “New Capitalism” policy to revive the economy.

The weak yen has boosted export earnings and profits for some of Japan’s largest corporations, in addition to helping the tourism industry exceed pre-pandemic levels. But higher-priced imports have further dampened consumption among ordinary Japanese, particularly those on fixed incomes and in irregular, low-paid, casual work.

Japan’s shrinking labour force also continues to exacerbate economic and social strains.

And just days ago, the decision by the Bank of Japan to raise interest rates to 0.25% triggered a wave of stock market volatility. The Nikkei index suffered its biggest drop since 1987, although it has largely recovered since then.

Despite Kishida’s considerable efforts to boost Japan’s alliances and a recent boost in defence spending, the country also faces an increasingly threatening security environment. This could become even more challenging if Donald Trump wins the US presidency in November.

Despite the recent missteps and scandals, the LDP is still likely to return to power in the next election, given the ongoing weakness of the main opposition Constitutional Democratic Party.

The next prime minister could then decide to hold a snap election this year, taking advantage of a brief honeymoon period to exploit the disunity among the opposition parties.

However, it will take a lot for any new leader to appeal to a Japanese public that is weary and jaded after years of political drama.![]()

Craig Mark, Adjunct Lecturer, Faculty of Economics, Hosei University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Japan Issues Megaquake Advisory After 7.1 Magnitude Earthquake

World's first wooden satellite built by Japan researchers

Japan to launch new banknotes on July 3

KDDI and Sharp to build Asia’s largest data centre

Japan wrestles with legacy of graft-stained Games in Paris warning

SoftBank to invest $960m in Japanese AI

OSAKA WANTS TO PLAY AT PARIS OLYMPICS 'IF THEY LET ME'

TOKYO - Former world number one Naomi Osaka said she "would love to play" at this year's Paris Olympics if she is granted a spot by tennis chiefs.

TOKYO - Former world number one Naomi Osaka said she "would love to play" at this year's Paris Olympics if she is granted a spot by tennis chiefs.Japan PM to visit Washington today

Record-breaking projections light up Tokyo skyscraper

Contaminated water leak at Fukushima Daiichi

.jpg?ext=.jpg)

Tokyo confirms record-high 949 new virus cases