Christin Hume – Unsplash

Christin Hume – UnsplashFrance Bans Forever Chemicals in Cosmetics, Fashion, and Ski Wax

Christin Hume – Unsplash

Christin Hume – UnsplashThe world’s carbon emissions continue to rise. But 35 countries show progress in cutting carbon

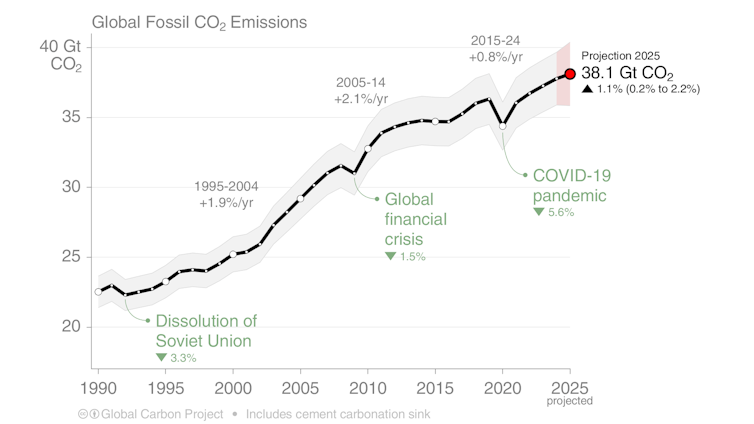

Global fossil fuel emissions are projected to rise in 2025 to a new all-time high, with all sources – coal, gas, and oil – contributing to the increase.

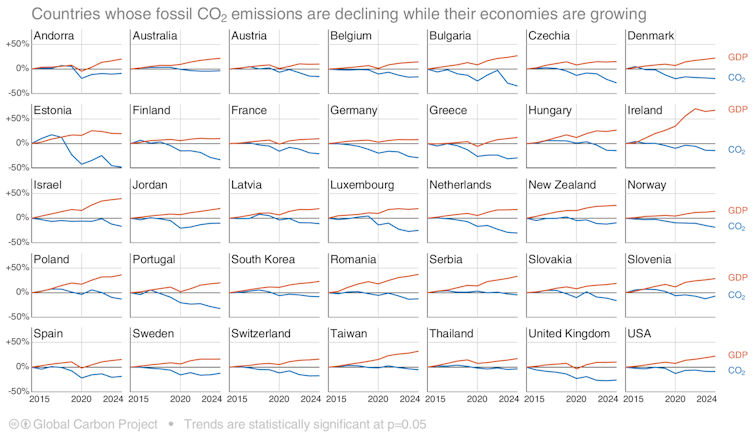

At the same time, our new global snapshot of carbon dioxide emissions and carbon sinks shows at least 35 countries have a plan to decarbonise. Australia, Germany, New Zealand and many others have shown statistically significant declines in fossil carbon emissions during the past decade, while their economies have continued to grow. China’s emissions have also been been growing at a much slower pace than recent trends and might even be flat by year’s end.

As world leaders and delegates meet in Brazil for the United Nations’ global climate summit, COP30, many countries that have submitted new emissions commitments to 2035 have shown increased ambition.

But unless these efforts are scaled up substantially, current global temperature trends are projected to significantly exceed the Paris Agreement target that aims to keep warming well below 2°C.

These 35 countries are now emitting less carbon dioxide even as their economies grow. Global Carbon Project 2025, CC BY-NC-ND

These 35 countries are now emitting less carbon dioxide even as their economies grow. Global Carbon Project 2025, CC BY-NC-NDFossil fuel emissions up again in 2025

Together with colleagues from 102 research institutions worldwide, the Global Carbon Project today releases the Global Carbon Budget 2025. This is an annual stocktake of the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide worldwide.

We also publish the major scientific advances enabling us to pinpoint the global human and natural sources and sinks of carbon dioxide with higher confidence. Carbon sinks are natural or artificial systems such as forests which absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they release.

Global CO₂ emissions from the use of fossil fuels continue to increase. They are set to rise by 1.1% in 2025, on top of a similar rise in 2024. All fossil fuels are contributing to the rise. Emissions from natural gas grew 1.3%, followed by oil (up 1.0%) and coal (up 0.8%). Altogether, fossil fuels produced 38.1 billion tonnes of CO₂ in 2025.

Not all the news is bad. Our research finds emissions from the top emitter, China (32% of global CO₂ emissions) will increase significantly more slowly below its growth over the past decade, with a modest 0.4% increase. Emissions from India (8% of global) are projected to increase by 1.4%, also below recent trends.

However, emissions from the United States (13% of global) and the European Union (6% of global) are expected to grow above recent trends. For the US, a projected growth of 1.9% is driven by a colder start to the year, increased liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, increased coal use, and higher demand for electricity.

EU emissions are expected to grow 0.4%, linked to lower hydropower and wind output due to weather. This led to increased electricity generation from LNG. Uncertainties in currently available data also include the possibility of no growth or a small decline.

Fossil fuel emissions hit a new high in 2025, but the growth rate is slowing and there are encouraging signs from countries cutting emissions. Global Carbon Project 2025, CC BY-NC-ND

Fossil fuel emissions hit a new high in 2025, but the growth rate is slowing and there are encouraging signs from countries cutting emissions. Global Carbon Project 2025, CC BY-NC-NDDrop in land use emissions

In positive news, net carbon emissions from changes to land use such as deforestation, degradation and reforestation have declined over the past decade. They are expected to produce 4.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2025 down from the annual average of 5 billion tonnes over the past decade. Permanent deforestation remains the largest source of emissions. This figure also takes into account the 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon soaked up by human-driven reforestation annually.

Three countries – Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – contribute 57% of global net land-use change CO₂ emissions.

When we combine the net emissions from land-use change and fossil fuels, we find total global human-caused emissions will reach 42.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2025. This total has grown 0.3% annually over the past decade, compared with 1.9% in the previous one (2005–14).

Carbon sinks largely stagnant

Natural carbon sinks in the ocean and terrestrial ecosystems remove about half of all human-caused carbon emissions. But our new data suggests these sinks are not growing as we would expect.

The ocean carbon sink has been relatively stagnant since 2016, largely because of climate variability and impacts from ocean heatwaves.

The land CO₂ sink has been relatively stagnant since 2000, with a significant decline in 2024 due to warmer El Niño conditions on top of record global warming. Preliminary estimates for 2025 show a recovery of this sink to pre-El Niño levels.

Since 1960, the negative effects of climate change on the natural carbon sinks, particularly on the land sink, have suppressed a fraction of the full sink potential. This has left more CO₂ in the atmosphere, with an increase in the CO₂ concentration by an additional 8 parts per million. This year, atmospheric CO₂ levels are expected to reach just above 425 ppm.

Tracking global progress

Despite the continued global rise of carbon emissions, there are clear signs of progress towards lower-carbon energy and land use in our data.

There are now 35 countries that have reduced their fossil carbon emissions over the past decade, while still growing their economy. Many more, including China, are shifting to cleaner energy production. This has led to a significant slowdown of emissions growth.

Existing policies supporting national emissions cuts under the Paris Agreement are projected to lead to global warming of 2.8°C above preindustrial levels by the end of this century.

This is an improvement over the previous assessment of 3.1°C, although methodological changes also contributed to the lower warming projection. New emissions cut commitments to 2035, for those countries that have submitted them, show increased mitigation ambition.

This level of expected mitigation falls still far short of what is needed to meet the Paris Agreement goal of keeping warming well below 2°C.

At current levels of emissions, we calculate that the remaining global carbon budget – the carbon dioxide still able to be emitted before reaching specific global temperatures (averaged over multiple years) – will be used up in four years for 1.5°C (170 gigatonnes remaining), 12 years for 1.7°C (525 Gt) and 25 years for 2°C (1,055 Gt).

Falling short

Our improved and updated global carbon budget shows the relentless global increase of fossil fuel CO₂ emissions. But it also shows detectable and measurable progress towards decarbonisation in many countries.

The recovery of the natural CO₂ sinks is a positive finding. But large year-to-year variability shows the high sensitivity of these sinks to heat and drought.

Overall, this year’s carbon report card shows we have fallen short, again, of reaching a global peak in fossil fuel use. We are yet to begin the rapid decline in carbon emissions needed to stabilise the climate.![]()

Pep Canadell, Chief Research Scientist, CSIRO Environment; Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO; Clemens Schwingshackl, Senior Researcher in Climate Science, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich; Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society Research Professor of Climate Change Science, University of East Anglia; Glen Peters, Senior Researcher, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo; Judith Hauck, Helmholtz Young Investigator group leader and deputy head, Marine Biogeosciences section at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Universität Bremen; Julia Pongratz, Professor of Physical Geography and Land Use Systems, Department of Geography, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich; Mike O'Sullivan, Lecturer in Mathematics and Statistics, University of Exeter; Pierre Friedlingstein, Chair, Mathematical Modelling of Climate, University of Exeter, and Robbie Andrew, Senior Researcher, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Over 2,000 flights cancelled across US as federal govt shutdown enters day 40

Representational photo. (IANS Photo)

Representational photo. (IANS Photo)New Rule Requires US Airlines to Give Automatic Refunds for Canceled or Delayed Flights and Late Baggage

By Hanson Lu

By Hanson LuWant more protein for less money? Don’t be fooled by the slick black packaging

If you’ve been supermarket shopping lately, you might have noticed more foods with big, bold protein claims on black packaging – from powders and bars to yoghurt, bread and even coffee.

International surveys show people are shopping for more protein because they think it’ll help their fitness and health. But clever marketing can sway our judgement too.

Before your next shop, here’s what you should know about how protein is allowed to be sold to us. And as a food and nutrition scientist, I’ll offer some tips for choosing the best value meat or plant-based protein for every $1 you spend – and no, protein bars aren’t the winner.

‘Protein’ vs ‘increased protein’ claims

Let’s start with those “high protein” or “increased protein” claims we’re seeing more of on the shelves.

In Australia and New Zealand, there are actually rules and nuances about how and when companies can use those phrases.

Under those rules, labelling a product as a “protein” product implies it’s a “source” of protein. That means it has at least 5 grams of protein per serving.

“High protein” doesn’t have a specific meaning in the food regulations, but is taken to mean “good source”. Under the rules, a “good source” should have at least 10 grams of protein per serving.

Then there is the “increased protein” claim, which means it has at least 25% more protein than the standard version of the same food.

If you see a product labelled as a “protein” version, you might assume it has significantly more protein than the standard version. But this might not be the case.

Take, for example, a “protein”-branded, black-wrapped cheese: Mini Babybel Protein. It meets the Australian and New Zealand rules of being labelled as a “source” of protein, because it has 5 grams of protein per serving (in this case, in a 20 gram serve of cheese).

But what about the original red-wrapped Mini Babybel cheese? That has 4.6g of protein per 20 gram serving.

The difference between the original vs “protein” cheese is not even a 10% bump in protein content.

Black packaging by design

Food marketers use colours to give us signals about what’s in a package.

Green signals natural and environmentally friendly, reds and yellows are often linked to energy, and blue goes with coolness and hydration.

These days, black is often used as a visual shorthand for products containing protein.

But it’s more than that. Research also suggests black conveys high-quality or “premium” products. This makes it the perfect match for foods marketed as “functional” or “performance-boosting”.

The ‘health halo’ effect

When one attribute of a food is seen as positive, it can make us assume the whole product is health-promoting, even if that’s not the case. This is called a “health halo”.

For protein, the glow of the protein halo can make us blind to the other attributes of the food, such as added fats or sugars. We might be willing to pay more too.

It’s important to know protein deficiency is rare in countries like Australia. You can even have too much protein.

How to spend less to get more protein

If you do have good reason to think you need more protein, here’s how to get better value for your money.

Animal-based core foods are nutritionally dense and high-quality protein foods. Meats, fish, poultry, eggs, fish, and cheese will have between 11 to 32 grams of protein per 100 grams.

That could give you 60g in a chicken breast, 22g in a can of tuna, 17g in a 170g tub of Greek yoghurt, or 12g in 2 eggs.

In the animal foods, chicken is economical, delivering more than 30g of protein for each $1 spent.

But you don’t need to eat animal products to get enough protein.

In fact, once you factor in costs – and I made the following calculations based on recent supermarket prices – plant-based protein sources become even more attractive.

Legumes (such as beans, lentils and soybeans) have about 9g of protein per 100g, which is about half a cup. Legumes are in the range of 20g of protein per dollar spent, which is a similar cost ratio to a protein powder.

Nuts and seeds like sunflower seeds can have 7g in one 30g handful. Even one cup of simple frozen peas will provide about 7g of protein.

Peanuts at $6 per kilogram supply 42g of protein for each $1 spent.

Dry oats, at $3/kg have 13g of protein per 100g (or 5g in a half cup serve), that’s 33g of protein per dollar spent.

In contrast, processed protein bars are typically poor value, coming in at between 6-8g of protein per $1 spent, depending on if you buy them in a single serve, or in a box of five bars.

Fresh often beats processed on price and protein

Packaged products offer convenience and certainty. But if you rely on convenience, colours and keywords alone, you might not get the best deals or the most nutritious choices.

Choosing a variety of fresh and whole foods for your protein will provide a diversity of vitamins and minerals, while reducing risks associated with consuming too much of any one thing. And it can be done without breaking the bank.![]()

Emma Beckett, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, Nutrition, Dietetics & Food Innovation - School of Health Sciences, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Changing rules of travel to Europe

Travellers using self sevice kiosk in the UK. Photo courtesy UK Times -

Travellers using self sevice kiosk in the UK. Photo courtesy UK Times -AI 171 crash preliminary report has found no mechanical or maintenance faults: Air India CEO

World Bank lifts ban on nuclear energy financing

Emotions run high as power outage shuts London's Heathrow

NPCI in talks to remove ‘pull transactions’ on UPI to reduce digital frauds

Adani Group’s ‘foray into industrial 5G’ is a complete failure

US-China trade war flares as both sides introduce new chip tech restrictions | Total Telecom

Namibia halts Starlink operations amid licensing dispute

Australia’s fertility rate has reached a record low. What might that mean for the economy?

Australia’s fertility rate has fallen to a new record low of 1.5 babies per woman. That’s well below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 needed to sustain a country’s population.

On face value, it might not seem like a big deal. But we can’t afford to ignore this issue. The health of an economy is deeply intertwined with the size and structure of its population.

Australians simply aren’t having as many babies as they used to, raising some serious questions about how we can maintain our country’s workforce, sustain economic growth and fund important services.

So what’s going on with fertility rates here and around the world, and what might it mean for the future of our economy? What can we do about it?

Are lower birth rates always a problem?

Falling fertility rates can actually have some short-term benefits. Having fewer dependent young people in an economy can increase workforce participation, as well as boost savings and wealth.

Smaller populations can also benefit from increased investment per person in education and health.

But the picture gets more complex in the long term, and less rosy. An ageing population can strain pensions, health care and social services. This can hinder economic growth, unless it’s offset by increased productivity.

Other scholars have warned that a falling population could stifle innovation, with fewer young people meaning fewer breakthrough ideas.

A global phenomenon

The trend towards women having fewer children is not unique to Australia. The global fertility rate has dropped over the past couple of decades, from 2.7 babies per woman in 2000 to 2.4 in 2023.

However, the distribution is not evenly spread. In 2021, 29% of the world’s babies were born in sub-Saharan Africa. This is projected to rise to 54% by 2100.

There’s also a regional-urban divide. Childbearing is often delayed in urban areas and late fertility is more common in cities.

In Australia, we see higher fertility rates in inner and outer regional areas than in metro areas. This could be because of more affordable housing and a better work-life balance.

But it raises questions about whether people are moving out of cities to start families, or if something intrinsic about living in the regions promotes higher birth rates.

Fewer workers, more pressure on services

Changes to the makeup of a population can be just as important as changes to its size. With fewer babies being born and increased life expectancy, the proportion of older Australians who have left the workforce will keep rising.

One way of tracking this is with a metric called the old-age dependency ratio – the number of people aged 65 and over per 100 working-age individuals.

In Australia, this ratio is currently about 27%. But according to the latest Intergenerational Report, it’s expected to rise to 38% by 2063.

An ageing population means greater demand for medical services and aged care. As the working-age population shrinks, the tax base that funds these services will also decline.

What about housing?

It’s tempting to think a falling birth rate might be good news for Australia’s stubborn housing crisis.

The issues are linked – rising real estate prices have made it difficult for many young people to afford homes, with a significant number of people in their 20s still living with their parents.

This can mean delaying starting a family and reducing the number of children they have.

At the same time, if fertility rates stay low, demand for large family homes may decrease, impacting one of Australia’s most significant economic sectors and sources of household wealth.

Can governments turn the tide?

Governments worldwide, including Australia, have long experimented with policies that encourage families to have more children. Examples include paid parental leave, childcare subsidies and financial incentives, such as Australia’s “baby bonus”.

Many of these efforts have had only limited success. One reason is the rising average age at which women have their first child. In many developed countries, including Australia, the average age for first-time mothers has surpassed 30.

As women delay childbirth, they become less likely to have multiple children, further contributing to declining birth rates. Encouraging women to start a family earlier could be one policy lever, but it must be balanced with women’s growing workforce participation and career goals.

Research has previously highlighted the factors influencing fertility decisions, including levels of paternal involvement and workplace flexibility. Countries that offer part-time work or maternity leave without career penalties have seen a stabilisation or slight increases in fertility rates.

The way forward

Historically, one of the ways Australia has countered its low birth rate is through immigration. Bringing in a lot of people – especially skilled people of working age – can help offset the effects of a low fertility rate.

However, relying on immigration alone is not a long-term solution. The global fertility slump means that the pool of young, educated workers from other countries is shrinking, too. This makes it harder for Australia to attract the talent it needs to sustain economic growth.

Australia’s record-low fertility rate presents both challenges and opportunities. On one hand, the shrinking number of young people will place a strain on public services, innovation and the labour market.

On the other hand, advances in technology, particularly in artificial intelligence and robotics, may help ease the challenges of an ageing population.

That’s the optimistic scenario. AI and other tech-driven productivity gains could reduce the need for large workforces. And robotics could assist in aged care, lessening the impact of this demographic shift.![]()

Jonathan Boymal, Associate Professor of Economics, RMIT University; Ashton De Silva, Professor of Economics, RMIT University, and Sarah Sinclair, Senior Lecturer in Economics, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

China hits tech firms with hefty fines as crackdown draws to close

Telia to slash 3,000 jobs in cost cutting drive

Telegram CEO Durov released on bail, but formally put under investigation

60 million americans under alert as heat wave hits US Midwest states

The Conversation,

The Conversation,