AT&T drops DEI to get $1bn spectrum deal approved

X-energy 'reserves' Doosan forgings

_56248.jpg)

Delta Airlines Treats Teens to Free ‘Dream Flights’ Inspiring Many to Become Pilots and Engineers

Delta’s 24th Dream Flight – credit, Delta Airlines

Delta’s 24th Dream Flight – credit, Delta AirlinesOver 2,000 flights cancelled across US as federal govt shutdown enters day 40

Representational photo. (IANS Photo)

Representational photo. (IANS Photo)New Rule Requires US Airlines to Give Automatic Refunds for Canceled or Delayed Flights and Late Baggage

By Hanson Lu

By Hanson LuA US startup plans to deliver ‘sunlight on demand’ after dark. Can it work – and would we want it to?

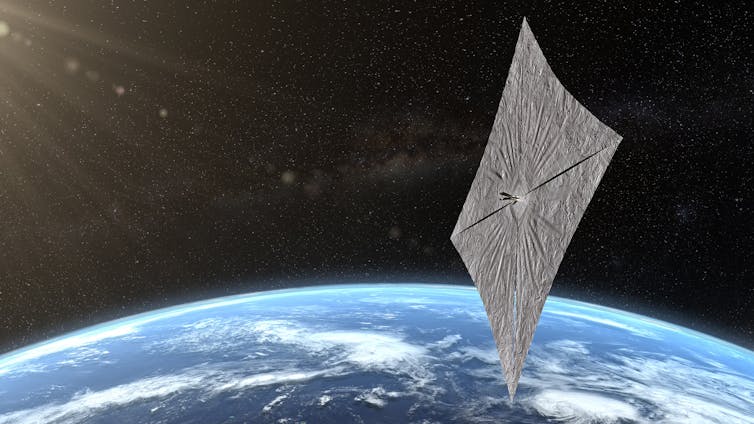

Can a new satellite constellation create sunlight on demand? SpaceX/Flickr, CC BY-ND

Michael J. I. Brown, Monash University and Matthew Kenworthy, Leiden University

Can a new satellite constellation create sunlight on demand? SpaceX/Flickr, CC BY-ND

Michael J. I. Brown, Monash University and Matthew Kenworthy, Leiden UniversityA proposed constellation of satellites has astronomers very worried. Unlike satellites that reflect sunlight and produce light pollution as an unfortunate byproduct, the ones by US startup Reflect Orbital would produce light pollution by design.

The company promises to produce “sunlight on demand” with mirrors that beam sunlight down to Earth so solar farms can operate after sunset.

It plans to start with an 18-metre test satellite named Earendil-1 which the company has applied to launch in 2026. It would eventually be followed by about 4,000 satellites in orbit by 2030, according to the latest reports.

So how bad would the light pollution be? And perhaps more importantly, can Reflect Orbital’s satellites even work as advertised?

Bouncing sunlight

In the same way you can bounce sunlight off a watch face to produce a spot of light, Reflect Orbital’s satellites would use mirrors to beam light onto a patch of Earth.

But the scale involved is vastly different. Reflect Orbital’s satellites would orbit about 625km above the ground, and would eventually have mirrors 54 metres across.

When you bounce light off your watch onto a nearby wall, the spot of light can be very bright. But if you bounce it onto a distant wall, the spot becomes larger – and dimmer.

This is because the Sun is not a point of light, but spans half a degree in angle in the sky. This means that at large distances, a beam of sunlight reflected off a flat mirror spreads out with an angle of half a degree.

What does that mean in practice? Let’s take a satellite reflecting sunlight over a distance of roughly 800km – because a 625km-high satellite won’t always be directly overhead, but beaming the sunlight at an angle. The illuminated patch of ground would be at least 7km across.

Even a curved mirror or a lens can’t focus the sunlight into a tighter spot due to the distance and the half-degree angle of the Sun in the sky.

Would this reflected sunlight be bright or dim? Well, for a single 54 metre satellite it will be 15,000 times fainter than the midday Sun, but this is still far brighter than the full Moon.

The balloon test

Last year, Reflect Orbital’s founder Ben Nowack posted a short video which summarised a test with the “last thing to build before moving into space”. It was a reflector carried on a hot air balloon.

In the test, a flat, square mirror roughly 2.5 metres across directs a beam of light down to solar panels and sensors. In one instance the team measures 516 watts of light per square metre while the balloon is at a distance of 242 metres.

For comparison, the midday Sun produces roughly 1,000 watts per square metre. So 516 watts per square metre is about half of that, which is enough to be useful.

However, let’s scale the balloon test to space. As we noted earlier, if the satellites were 800km from the area of interest, the reflector would need to be 6.5km by 6.5km – 42 square kilometres. It’s not practical to build such a giant reflector, so the balloon test has some limitations.

So what is Reflect Orbital planning to do?

Reflect Orbital’s plan is “simple satellites in the right constellation shining on existing solar farms”. And their goal is only 200 watts per square metre – 20% of the midday Sun.

Can smaller satellites deliver? If a single 54 metre satellite is 15,000 times fainter than the midday Sun, you would need 3,000 of them to achieve 20% of the midday Sun. That’s a lot of satellites to illuminate one region.

Another issue: satellites at a 625km altitude move at 7.5 kilometres per second. So a satellite will be within 1,000km of a given location for no more than 3.5 minutes.

This means 3,000 satellites would give you a few minutes of illumination. To provide even an hour, you’d need thousands more.

Reflect Orbital isn’t lacking ambition. In one interview, Nowack suggested 250,000 satellites in 600km high orbits. That’s more than all the currently catalogued satellites and large pieces of space junk put together.

And yet, that vast constellation would deliver only 20% of the midday Sun to no more than 80 locations at once, based on our calculations above. In practice, even fewer locations would be illuminated due to cloudy weather.

Additionally, given their altitude, the satellites could only deliver illumination to most locations near dusk and dawn, when the mirrors in low Earth orbit would be bathed in sunlight. Aware of this, Reflect Orbital plan for their constellation to encircle Earth above the day-night line in sun-synchronous orbits to keep them continuously in sunlight.

Bright lights

So, are mirrored satellites a practical means to produce affordable solar power at night? Probably not. Could they produce devastating light pollution? Absolutely.

In the early evening it doesn’t take long to spot satellites and space junk – and they’re not deliberately designed to be bright. With Reflect Orbital’s plan, even if just the test satellite works as planned, it will sometimes appear far brighter than the full Moon.

A constellation of such mirrors would be devastating to astronomy and dangerous to astronomers. To anyone looking through a telescope the surface of each mirror could be almost as bright as the surface of the Sun, risking permanent eye damage.

The light pollution will hinder everyone’s ability to see the cosmos and light pollution is known to impact the daily rhythms of animals as well.

Although Reflect Orbital aims to illuminate specific locations, the satellites’ beams would also sweep across Earth when moving from one location to the next. The night sky could be lit up with flashes of light brighter than the Moon.

The company did not reply to The Conversation about these concerns within deadline. However, it told Bloomberg this week it plans to redirect sunlight in ways that are “brief, predictable and targeted”, avoiding observatories and sharing the locations of the satellites so scientists can plan their work.

The consequences would be dire

It remains to be seen whether Reflect Orbital’s project will get off the ground. The company may launch a test satellite, but it’s a long way from that to getting 250,000 enormous mirrors constantly circling Earth to keep some solar farms ticking over for a few extra hours a day.

Still, it’s a project to watch. The consequences of success for astronomers – and anyone else who likes the night sky dark – would be dire. ![]()

Michael J. I. Brown, Associate Professor in Astronomy, Monash University and Matthew Kenworthy, Associate Professor in Astronomy, Leiden University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Oklo announces plans for Tennessee fuel recycling plant

_35510.jpg)

Georgia clears debts to seven countries, including Armenia

.jpg)

Madonna pens heartwarming note on son David’s birthday: I knew you were meant for greatness

World Athletics C'ships: United States wins three of four relay titles on final day in Tokyo

US Open: Sinner dominates Bublik for 8th consecutive Grand Slam QF

Man Wracks Up 250,000 EV Miles Driving Neighbors in Need–and the Battery Still Has a Capacity of 92%

Good neighbor David Blenkle in his 2022 Mustang Mach-E

Good neighbor David Blenkle in his 2022 Mustang Mach-E David Blenkle -credit Ford

David Blenkle -credit FordWHO restructures, cuts budget after US withdrawal

The 78th World Health Assembly was held at the United Nations in Geneva

The 78th World Health Assembly was held at the United Nations in GenevaWalsh swims second-fastest 100m butterfly in history

CHICAGO - Gretchen Walsh clocked a stunning 54.76sec to win the 100m butterfly at the US Swimming Championships on Thursday, coming up just shy of her own world record in a comfortable victory over Olympic champion Torri Huske.

Canada, US, Mexico brace for World Cup extravaganza

The US and China have reached a temporary truce in the trade wars, but more turbulence lies ahead

Peter Draper, University of Adelaide and Nathan Howard Gray, University of Adelaide

Defying expectations, the United States and China have announced an important agreement to de-escalate bilateral trade tensions after talks in Geneva, Switzerland.

The good, the bad and the ugly

The good news is their recent tariff increases will be slashed. The US has cut tariffs on Chinese imports from 145% to 30%, while China has reduced levies on US imports from 125% to 10%. This greatly eases major bilateral trade tensions, and explains why financial markets rallied.

The bad news is twofold. First, the remaining tariffs are still high by modern standards. The US average trade-weighted tariff rate was 2.2% on January 1 2025, while it is now estimated to be up to 17.8%. This makes it the highest tariff wall since the 1930s.

Overall, it is very likely a new baseline has been set. Bilateral tariff-free trade belongs to a bygone era.

Second, these tariff reductions will be in place for 90 days, while negotiations continue. Talks will likely include a long list of difficult-to-resolve issues. China’s currency management policy and industrial subsidies system dominated by state-owned enterprises will be on the table. So will the many non-tariff barriers Beijing can turn on and off like a tap.

China is offering to purchase unspecified quantities of US goods – in a repeat of a US-China “Phase 1 deal” from Trump’s first presidency that was not implemented. On his first day in office in January, amid a blizzard of executive orders, Trump ordered a review of that deal’s implementation. The review found China didn’t follow through on the agriculture, finance and intellectual property protection commitments it had made.

Unless the US has now decided to capitulate to Beijing’s retaliatory actions, it is difficult to see the US being duped again.

Failure to agree on these points would reveal the ugly truth that both countries continue to impose bilateral export controls on goods deemed sensitive, such as semiconductors (from the US to China) and processed critical minerals (from China to the US).

Moreover, in its so-called “reciprocal” negotiations with other countries, the US is pressing trading partners to cut certain sensitive China-sourced goods from their exports destined for US markets. China is deeply unhappy about these US demands and has threatened to retaliate against trading partners that adopt them.

A temporary truce

Overall, the announcement is best viewed as a truce that does not shift the underlying structural reality that the US and China are locked into a long-term cycle of escalating strategic competition.

That cycle will have its ups (the latest announcement) and downs (the tariff wars that preceded it). For now, both sides have agreed to announce victory and focus on other matters.

For the US, this means ensuring there will be consumer goods on the shelves in time for Halloween and Christmas, albeit at inflated prices. For China, it means restoring some export market access to take pressure off its increasingly ailing economy.

As neither side can vanquish the other, the likely long-term result is a frozen conflict. This will be punctuated by attempts to achieve “escalation dominance”, as that will determine who emerges with better terms. Observers’ opinions on where the balance currently lies are divided.

Along the way, and to use a quote widely attributed to Winston Churchill, to “jaw-jaw is better than to war-war”. Fasten your seat belts, there is more turbulence to come.

Where does this leave the rest of us?

Significantly, the US has not (so far) changed its basic goals for all its bilateral trade deals.

Its overarching aim is to cut the goods trade deficit by reducing goods imports and eliminating non-tariff barriers it says are “unfairly” prohibiting US exports. The US also wants to remove barriers to digital trade and investments by tech giants and “derisk” certain imports that it deems sensitive for national security reasons.

The agreement between the US and UK last week clearly reflects these goals in operation. While the UK received some concessions, the remaining tariffs are higher, at 10% overall, than on April 2 and subject to US-imposed import quotas. Furthermore, the UK must open its market for certain goods while removing China-originating content from steel and pharmaceutical products destined for the US.

For Washington’s Pacific defence treaty allies, including Australia, nothing has changed. Potentially difficult negotiations with the Trump administration lie ahead, particularly if the US decides to use our security dependencies as leverage to wring concessions in trade. Japan has already disavowed linking security and trade, and their progress should be closely watched.

The US has previously paused high tariffs on manufacturing nations in South-East Asia, particularly those used by other nations as export platforms to avoid China tariffs. Vietnam, Cambodia and others will face sustained uncertainty and increasingly difficult balancing acts. The economic stakes are higher for them.

They, like the Japanese, are long-practised in the subtle arts of balancing the two giants. Still, juggling ties with both Washington and Beijing will become the act of an increasingly high-wire trapeze artist.![]()

Peter Draper, Professor, and Executive Director: Institute for International Trade, and Jean Monnet Chair of Trade and Environment, University of Adelaide and Nathan Howard Gray, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for International Trade, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The global costs of the US-China tariff war are mounting. And the worst may be yet to come

The United States and China remain in a standoff in their tariff war. Neither side appears willing to budge.

After US President Donald Trump imposed massive 145% tariffs on Chinese imports in early April, China retaliated with its own tariffs of 125% on US goods.

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said this week it’s up to China to de-escalate tensions. China’s Foreign Ministry, meanwhile, said the two sides are not talking.

The prospect of economic decoupling between the world’s two largest economies is no longer speculative. It is becoming a hard reality. While many observers debate who might “win” the trade war, the more likely outcome is that everyone loses.

A convenient target

Trump’s protectionist agenda has spared few. Allies and adversaries alike have been targeted by sweeping US tariffs. However, China has served as the main target, absorbing the political backlash of broader frustrations over trade deficits and economic displacement in the US.

The economic costs to China are undeniable. The loss of reliable access to the US market, coupled with mounting uncertainty in the global trading system, has dealt a blow to China’s export-driven sectors.

China’s comparative advantage lies in its vast manufacturing base and tightly integrated supply chains. This is especially true in high-tech and green industries such as electric vehicles, batteries and solar energy. These sectors are deeply dependent on open markets and predictable demand.

New trade restrictions in Europe, Canada and the US on Chinese electric vehicles, in particular, have already caused demand to drop significantly.

China’s GDP growth was higher than expected in the first quarter of the year at 5.4%, but analysts expect the effect of the tariffs to soon bite. A key measure of factory activity this week showed a contraction in manufacturing.

China’s economic growth has also been weighed down by structural headwinds, including industrial overcapacity (when a country’s production of goods exceeds demand), an ageing population, rising youth unemployment and persistent regional disparities. The property sector — once a pillar of the country’s economic rise — has become a source of financial stress. Local government debt is mounting and a pension crisis is looming.

Negotiations with the US might be desirable to end the tariff war. However, unilateral concessions on Beijing’s part are neither viable nor politically palatable.

Regional coordination

Trump’s tariff wars have done more than strain bilateral relationships; they have shaken the foundations of the global trading system.

By sidelining the World Trade Organization and embracing a transactional approach to bilateral trade, the US has weakened multilateral norms and emboldened protectionist tendencies worldwide.

One unintended consequence of this instability has been the resurgence of regional arrangements. In Asia, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), backed by China and centred on the ASEAN bloc in Southeast Asia, has emerged as a credible alternative for economic cooperation.

Meanwhile, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) continues to expand, with the United Kingdom joining late last year.

Across Latin America, too, regional blocs are exploring new avenues for integration, hoping to buffer themselves against the shocks of resurgent protectionism.

But regionalism is no panacea. It cannot replicate the scale or efficiency of global trade, nor can it restore the predictability on which exporters depend.

Looming dangers

The greater danger is the world drifting into a Kindleberger Trap — a situation in which no power steps forward to provide the leadership necessary to sustain global public goods, or a stable trading system.

Economist Charles Kindleberger’s account of the Great Depression remains instructive: it was not the presence of conflict but the absence of leadership that brought about the global economy’s systemic collapse.

Without renewed global coordination, the economic fragmentation triggered by Trump’s tariff wars could give way to something far more dangerous than a recession – rising geopolitical and military tensions that no region can contain.

The political landscape is already fraught. The Chinese Communist Party, for instance, has long tethered its legitimacy to the promise of eventual unification with Taiwan. Yet the costs of using force remain prohibitively high.

Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te’s recent designation of China as a “foreign hostile force” have sharpened tensions. Beijing’s response has been calibrated – military exercises intended more as a warning than a prelude to conflict.

However, the intensifying trade war with the US may become the final straw that exhausts Beijing’s patience, leaving Taiwan as collateral damage in a US-China final showdown.

A role for collective leadership

China alone is neither able nor inclined to assume the mantle of global leadership. Its current focus is more on domestic priorities – sustaining economic growth and managing social stability – than on foreign policy.

Yet, Beijing can still play a constructive role in shaping the international environment through its cooperation with Europe, ASEAN and the Global South.

The objective is not to replace American hegemony, but to support a more multi-polar and collaborative system — one capable of sustaining global public goods in an era of uncertainty.

Paradoxically, a more coordinated effort by the rest of the world may ultimately help bring the US back into the fold. Washington may rediscover the strategic value of engagement — and return not as the sole leader, but as an indispensable partner.

In the short term, other states may seek to gain an advantage from the great power standoff. But they should remember that what begins as a clash between giants can quickly engulf bystanders.

In this volatile landscape, the path forward does not lie in exploiting disorder. Rather, nations must cautiously advance the shared interest in restoring a stable, rules-based global order.![]()

Kai He, Professor of International Relations, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Intelsat and AXESS Networks extend partnership to boost satellite coverage across the Americas

Where things stand in the US-China trade war